Failures in legislation and risk management

The mad mental health policy

09 Feb 2026

This article was initially published in The Critic.

At the end of January, court proceedings resume against Anthony Williams, the man who randomly stabbed 10 members of the public on a train near Huntingdon in November last year. At the time of the tragedy, some suspected Williams of being a terrorist. But his actions resembled the attacks carried out by Axel Rudakubana, who murdered three young girls in Southport last year, and of Valdo Calocane who fatally stabbed three people in Nottingham in 2023.

In each of these instances it is likely that severe mental health issues were a contributing, if not the decisive factor behind the violence. Both Rudakubana and Calocane were known to mental health services. Williams was known to the police and is being linked with three other knife incidents. If relevant agencies were aware of the underlying health concerns in each instance, why were they unable to prevent these tragedies?

Whilst the Southport inquiry is still ongoing and there will doubtless be an investigation into Williams, the independent investigation into the care and treatment provided to Calocane is instructive. Commissioned by NHS England, the report shows that Calocane was first arrested three years before his attack and subjected to a mental health assessment before being sent home.

Between this first arrest in 2020 and 2023, Calocane was shuffled around between the police, hospitals and mental health services. He was admitted to hospital four times, detained multiple times under Sections 2 and 3 of the Mental Health Act and discharged back into the community under the voluntary care of multiple Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) teams.

Reading through the report, it becomes apparent that the emphasis on autonomy in our current system makes it very difficult for the health services to manage people with violent or aggressive tendencies. Not least because records show that Calocane did not consider himself to be suffering from a mental health condition and potentially didn’t consider his mental state to be abnormal.

This meant that although Calocane did subscribe to treatment whilst in hospital, it became much more difficult to attest to whether he was still taking medication once discharged. The report notes that in the summer of 2022, the EIP team were having difficulty in contacting Calocane and providing him with medication.

◆

Despite Calocane’s history of violence and unpredictable behaviour being well documented by his care providers, detention under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act (MHA) is only possible for up to 28 days. After being discharged Calocane was no longer considered to be under Section 2 of the Act, meaning his continued engagement with mental health services was voluntary.

Calocane was also detained separately under Section 3 of the MHA, which allows for detention for up to six months, and the investigation does point out that there may have been a missed opportunity to implement a Community Treatment Order. This allows for someone to be discharged providing they comply with certain requirements such as taking medication or risk being recalled to hospital.

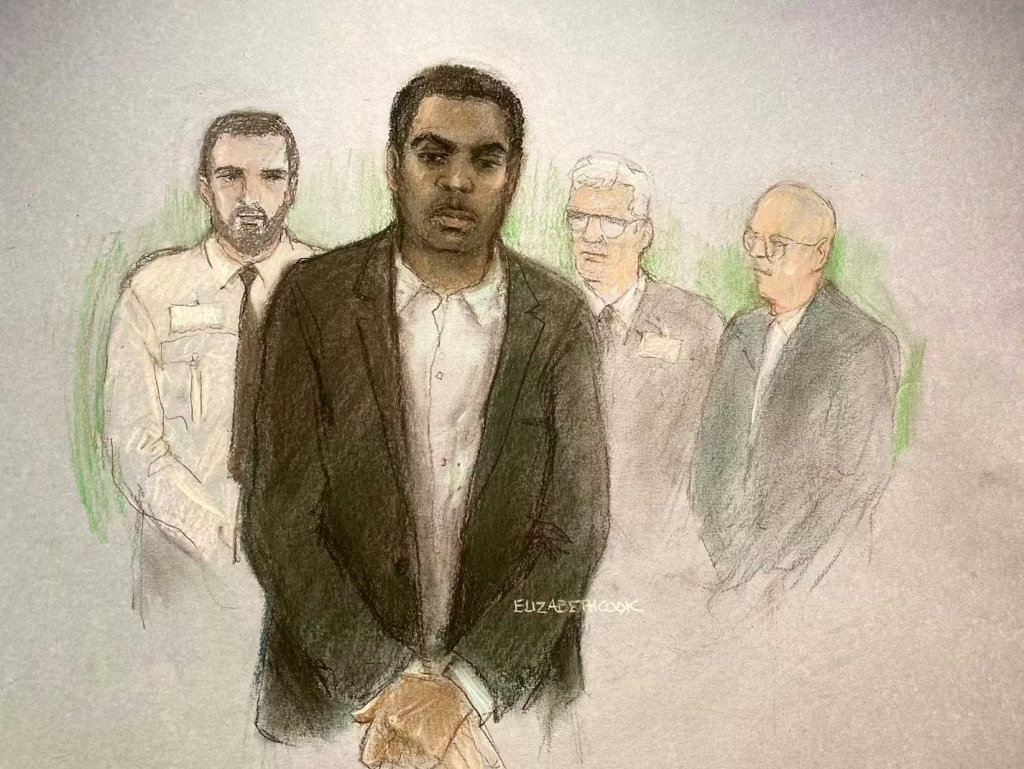

Valdo Calocane, sketched in court by Elizabeth Cook

Additionally, failures in the discharge process and record-keeping made it harder for the various bodies involved in Calocane’s care to properly assess his state and the risks he posed. But more importantly, the investigation notes that the use of “assertive outreach” — an approach that allows for a more intrusive model of care for people with severe mental illnesses — has effectively been disbanded across our care system, with what limited resources remaining being constrained by staff workload.

Without the assertive outreach to ensure that a severely mentally ill person is actually taking medication, it is difficult to see how a community care model can work for an individual with a known history of violent and unpredictable behaviour. Rather than receiving adequate support, their mental health deteriorates until they cause harm to themselves or others, requiring the involvement of the police. This happened to Calocane on at least one prior occasion.

This unstable pattern of detention and discharge continues across the country, with one predictable outcome being the random and extreme violence with which we have become depressingly familiar.

◆

One might immediately assume this is all downstream of a progressive ideological capture of both healthcare and the justice system. But it was Enoch Powell’s “water tower” speech in 1961 that first called for a move away from the institutionalisation of mental health patients, prompted by advancements in psychiatric drugs and the growing discomfort over conditions in Britain’s mental asylums.

Several major scandals involving abuse and neglect in asylums came to light over the course of the 60s and early 70s, particularly after the publication of Barbara Robb’s book Sans Everything documenting inadequate levels of care and the Ely Hospital scandal in Cardiff in 1967.

In 1971, a government white paper titled “Better Services for the Mentally Handicapped” outlined a plan for moving towards a community care model, in which residential services would become the norm with hospital treatment as and when required. Responding to the 1972 inquiry into Whittingham Hospital, the then Secretary of State for Social Services, Keith Joseph, acknowledged the need to transition away from the institutionalisation of mental health patients in psychiatric hospitals.

The plan was picked up by the Thatcher government, which oversaw the ultimate closure of asylums as part of the care in the community policy, seeking to instead treat patients in their homes wherever possible.

“Care in the community” may have a left-wing ring to it, but its conservative principles should be apparent: reduce reliance on the state, emphasise family and community responsibility. Yet from the outset, concerns were raised about resources and dangers. The situation and underlying conditions have only worsened since Thatcher’s day. It’s unlikely she could have ever foreseen our current straits.

From 2012-2022 mental health patients constituted 11 per cent of all homicide convictions in the United Kingdom, an average of 60 per year. Though the data is patchy, work done by the Hundred Families charity shows that approximately 400 people were killed by mental health patients between 2018-2023. Due to the nature of data collection, the organisation considers this to be an underestimate.

For over half a century, policymakers have pushed for greater patient autonomy at the expense of public safety. Though aspects of this approach are periodically criticised by politicians, deinstitutionalisation is very much the only direction of travel in mental health policy.

◆

The Government’s new Mental Health Act has just passed into law. It further enshrines patient choice and autonomy, cuts the time someone can be detained under Section 3 of the previous MHA and raises the thresholds for detention. It will also ban the authorities from using prisons and police cells as places to hold individuals whilst mental health assessments are carried out. And whilst the acute shortages in prison spaces will have no doubt influenced the decision, it remains as much driven by ideology as by circumstance.

Absent from the new legislation are any public safety measures, such as requiring assessments of the level of risk a discharged individual might pose to the community. Such an amendment was put forward by the opposition but has been dismissed by the government.

The changes will put even more pressure on health services to shuffle individuals around whilst limiting the options available to detain mentally ill people with violent tendencies. Given the fiscal outlook, cries for more funding to support these services are unlikely to be met any time soon.

Contemplating serious reform also requires addressing the racial disparities in violence relating to mental illness. Over the past five years, most of the mass stabbings in Britain perpetrated by people with severe mental health illnesses were committed by black men: aside from Williams, Rudakubana and Calocane, Joshua Jacques killed four people in Bermondsey in 2022, and Zephaniah McLeod killed one person and hurt seven others in Birmingham in 2020.

NHS England data records black men as almost ten times more likely to screen positive for a psychotic disorder than white men. There may be multiple reasons for this disparity, ranging from drug usage to an inability to integrate.

One important study (East London First-Episode Psychosis Study, reported in the Archives of General Psychiatry) shows that the risk of psychoses between first generation immigrants and the next generation appears to be similar, whilst the risk of nonaffective psychoses (such as schizophrenia) was higher in second-generation black Caribbeans. This suggests that in some cases successive generations pose a similar if not greater risk to themselves and the public, something that runs counter to many assumptions about the dynamics of integration.

Black people are also almost 3.5 times as likely as white people to be detained under the Mental Health Act, something the government views as a racial disparity that needs to be addressed. But as the Calocane investigation showed, release back into community care is fraught with risk, especially given the high emphasis placed on patient autonomy.

◆

Could permanent institutionalisation be brought back for individuals deemed most at risk to themselves or the public? Perhaps, though any return to mass institutionalisation will be a challenge politically. There were very good reasons behind the closure of the asylum system. This is before we even consider funding. The average annual cost of one place in a medium security hospital is £165,000. In a high security hospital this rises to £300,000.

In the Netherlands, a greater effort is made to protect society from recidivism by offenders with severe mental disorders. The Dutch TBS system allows courts to impose penal hospital orders on top of prison sentences in cases where offenders are deemed only partly accountable for their offences due to mental health conditions.

In England, such a system might have allowed Williams, Rudakubana or Calocane to have been detained for earlier offences and placed under a more restrictive regime — though one that still aims to rehabilitate where possible.

Addressing this challenge will require some creative and likely provocative thinking. This might include deprioritising other mental health services to free up capacity. It could involve relocating violent mental health patients to countries where facilities and adequate care can be provided at significantly reduced cost. Or more fundamentally, treating the issue as less of a medical and more of a criminal problem. And this is to say nothing of grappling with upstream causes.

What is clear is that a greater emphasis on risk management is urgently needed, which may include some level of permanent detention for those presenting indefinite danger to themselves or the public. Instead, the new Mental Health Act puts the relentless pursuit of patient autonomy above all else, weakening what few powers of detention remain. Alas, ignoring the relationship between this approach and mental health-related violence only makes future tragedies a more likely outcome.